Bustle: How This Artist Is Using Tarot Cards To Manifest A Hopeful Future

By Michelle Toglia

Published on Bustle.com on June 16, 2022

Artist Adrienne Elise Tarver had been interested in tarot for years, but she never really saw how the practice could fit into her artwork. But all that changed in mid-2020 amid Black Lives Matters protests and the ongoing pandemic. “It was like this veil between these things that we didn't talk about before [was lifted],” says Tarver of the summer of 2020. “Our real-life became so thin and permeable, that this idea of talking about spirituality, the future, and terror, felt much more serious. It felt like a necessary investigation for myself, and a necessary conversation for me to have.” Soon after, Manifesting Paradise — a hopeful, tarot-inspired project that looks to the future — was born.

Going through the tarot deck, Tarver began to see how each card’s meaning was reflected in her own life. “It's less about trying to predict the future, and it's more about trying to understand how you're... generalizing the present and how that might affect your future,” the Brooklyn-based artist tells Bustle.

The artwork is currently on display at an exhibition in the Academy Art Museum in Easton, Maryland until July 24. But Tarver’s not done with tarot just yet. “I'm going to keep going until I complete all 78 cards,” Tarver says. “There will be a full deck.” Below, Tarver shares three pieces from the project that hold special meaning.

HIGH PRIESTESS

This was one of the earliest ones. I felt like, oh this is good, this is going somewhere, this is the piece I want to put out into the world. Its number in the deck is two, but it's actually the third card because the first card is zero. The High Priestess is this figure, a traditionally feminine figure, that has a high sense of intuition and doesn't need to see things to know things. When I was starting to commit to making this series at the beginning of the pandemic, it felt like I was listening to all this information and couldn't really see what the future held, but I felt deeply that I wanted to know the things were going to be OK. I think [High Priestess] really embodied that feeling for me.

When people see High Priestess, I hope that there's a sense of calm. There's water over her eyes, and hearing people's interpretation of it is pretty spot on. There's this understanding that she's not blind, somehow she's still knowledgeable. I wouldn't say she’s all-knowing necessarily, but she's still knowledgeable. She's still in touch, even without her sight. It's kind of like the cliche, don't believe everything you see.

STRENGTH

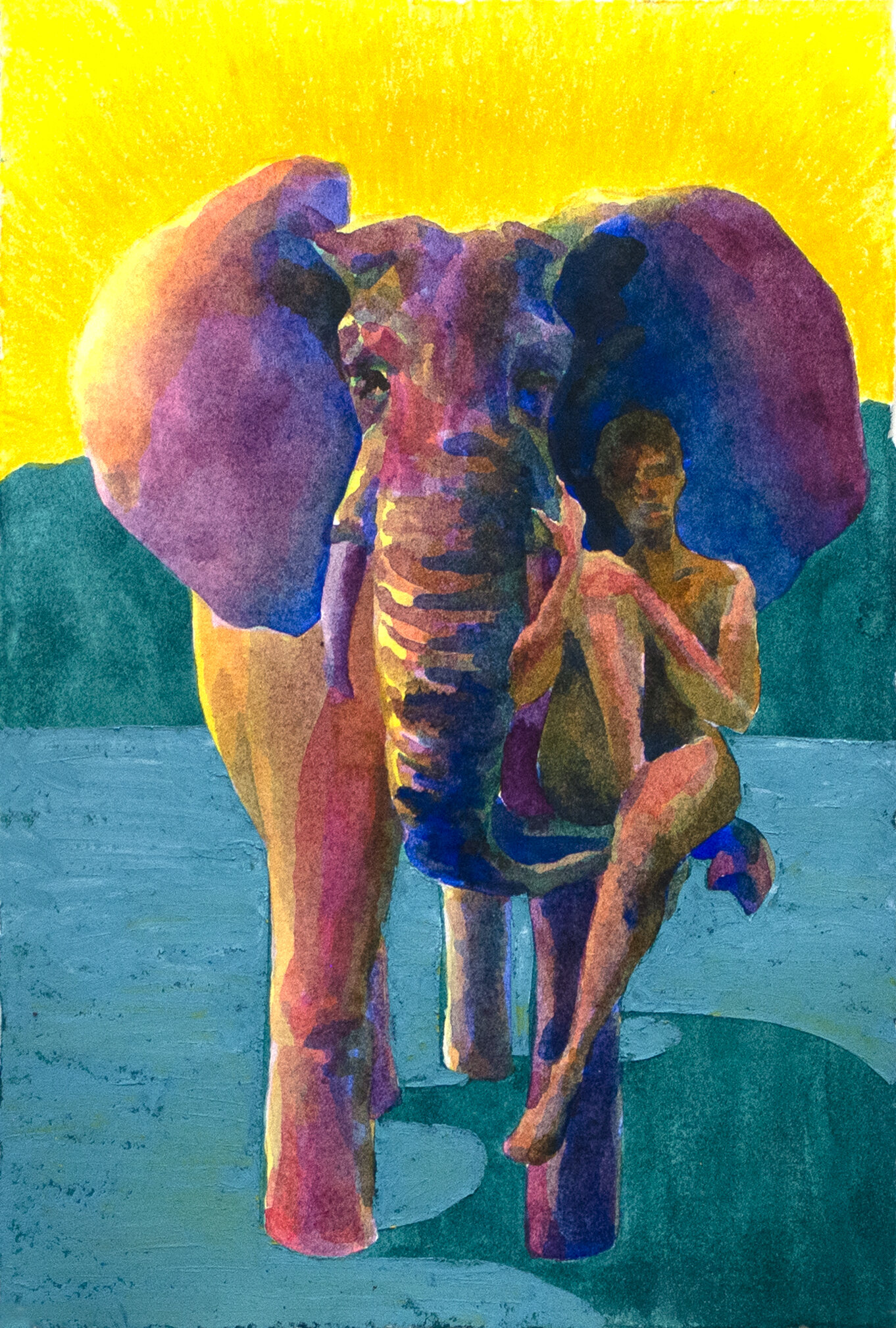

The Strength card has a special meaning to me because the imagery actually comes from a painting I made right out of undergrad. It’s this very big painting in my parents' house of this woman who's riding an elephant's trunk. She's not on the top of the elephant, but on its trunk and they're kind of walking together. Traditionally in tarot, the Strength card has a woman who's taming a lion or holding a lion's mouth.

But I love elephants — I think they're incredible animals. They're super intelligent and emotional. They run like matriarchal groups. There's this whole female-centered system that's natural to how they structure themselves. But they're also super intimidating because they're huge, they're heavy, and they can destroy things. So there's this gentle strength because they’re actually very sensitive animals, along with their physical presence.

Because of this fascination with them when I was younger, I made this painting. I recognized how it suited the card and this idea of strength so well. The interpretation of Strength, for me, is not about physical strength. It's about sustaining strength over a period. It's about the intelligence, the emotional intelligence, that’s needed to persevere in life.

TOWER

Tower is notoriously a difficult card, and nobody wants it to come up in their reading. I've never seen a tarot reader be able to give it a great spin. It's about destruction and necessary upheaval, and usually, it’s one that’s a surprise. Traditionally, its [symbol] is a medieval tower that's struck by lightning. The tower's on fire, and people are jumping out of it. I was really struggling to figure out how to interpret it for myself. You don't really want to think about the possibility of surprise destruction in your own life.

At the time, I was living in Atlanta and I was doing research on my own family history connected to the city. I had found images of the former Tarver Plantation that still stands. The history of this country didn't really allow for documenting Black people, but there's the possibility our family was connected. There were all these real estate images of it from the ‘90s that I printed out and had in my studio. This was the same time as protests were happening during the pandemic. So, we're talking about justice for violence against Black people in this space that has such a history of incredible violence — the soil itself is filled with bodies. Understanding what that meant there felt palpable.

Because I have this family history, I started to recognize that the necessary upheaval and destruction was this plantation house. It was this recognition of where it personally resonated with me, and also this understanding of how to find the silver lining of this card. I see how it can be maybe not positive but necessary.

Working on this felt a little cathartic. But also, I was kind of scared. It sounds silly because I wasn't actually burning down a house. It was just in concept. But I think this system is so ingrained in who we are as a country. And these plantations, which are everywhere in the south, they're kind of revered — people have weddings and parties there. They’ve been repurposed and their narrative has changed. They’ve kind of gotten a PR bump.

I lived in Georgia for seven years as a kid. These landscapes and things like plantation houses are ingrained in my memory in a positive way. I see the beauty of these places, so it's complicated in my memory. It almost felt like a betrayal [to make]. But part of me had to recognize that I had to let go of feeling bad about it because it's necessary. This is actually the thing that's destructive — and destroying it is what allows you to move on.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

ADRIENNE ELISE TARVER: The artist on how tarot impacted her work and the power of place.

Adrienne Elise Tarver is getting personal. After years of keeping a distance between her own history and her work, Tarver is unabashedly incorporating herself and the places she's called home into her practice. From her studio in Brooklyn, the artist spoke with Platform about what sparked that creative shift, her interest in tarot, and the unique ability of physical space to give us perspective on our life and work.

PLATFORM

Labels have a tendency to stick a lot when it comes to art, but I’m curious to hear from you what you feel your work is really about.

ADRIENNE

Subject-wise, the easy way I've distilled it is this: it's about the perception and identity of Black women. I've previously said things about Black women in the context of the Western landscape, or I've talked about the perception and identity of women in America. But I honestly think it's broader than that. So, I would just put the period after Black women.

PLATFORM

How has it become broader, do you feel?

ADRIENNE

I think, as with the more recent series Manifesting Paradise, it's sort of about tarot and the spiritual aspect of it really draws on these ideas of Black women as representing spiritual matriarchs and the world landscape. The reason I think I initially had it more narrow to the Western, American landscape is because that's my context and the identity that I've had to deal with. But I think there's so much influence, especially in our age of digital technology and the internet, that's wrapped around the global landscape. I think the conversation I'm having is a bit broader, but I'm starting in the identity that I exist in, which is American.

PLATFORM

I’m wondering if you could expand on how you think technology has changed that for you.

ADRIENNE

Well, it's funny with this whole tarot series. I've been thinking about tarot for a long time. It's one of those things that was in the background. It was a bit of a guilty pleasure until I was like, "What am I feeling guilty about? I think it's legitimate to be interested in this thing.” And I started to dissect why I was interested in it and this idea of the way I've framed it or thought about it. I think it's very generational in that earlier generations largely relied on religion to answer unknown questions. It's not uncommon or unheard of for people to want to draw answers about things that are difficult and confusing and unknown. Especially amidst the pandemic and political turmoil, there's this tendency to want to hold onto something larger.

And that can be a framework for creating answers. I think as we've moved away from churches and organized religion, the resurgence of things like psychics and tarot and crystals is not unique. I think it's a substitute inserting itself into the same place. This stuff isn't new, but it's reemerging at a time of technology where we're also contending with algorithms that are trying to get to know us and understand us and answer our unknown questions. One of the questions I ask myself as I'm thinking about these things in my daily life is: Is this an omen or is this an algorithm? How am I experiencing this thing? You want to believe, “I'm seeing this thing a million times. It means it's meant to be . . . but also Instagram's listening to me.”

PLATFORM

That's a huge question! Is it an omen or an algorithm?

ADRIENNE

You can apply it to so many things because there's a point where the algorithm's artificial intelligence has become so advanced and integrated that it's really hard to figure out where it stops. I think you have to be in the woods in the middle of nowhere with absolutely no technology on you to really believe that there's no algorithm at work to influence your existence at that moment.

PLATFORM

What made you want to integrate that into your work?

ADRIENNE

The shift from it being a fun thing I think about sometimes and talk about with friends to being in my work was really caused by the pandemic. I was like, “The world feels like it's ending. This thing doesn't feel lighthearted anymore.” Thinking about the future feels radical. And especially as a Black woman, as a Black person, as somebody in America, all of that felt radical. I mean, it still feels like the world might end tomorrow. It became much more of an anxiety that was coming to life in a real way, as opposed to the fun thing you do to find out if somebody likes you or if you're going to get that raise or that work's going to sell.

PLATFORM

Kind of piggybacking off of some of what you said, how people are represented is such a huge and complex issue in the history of art, especially, as you said, with Black women in particular. What are some of the aspects related to that that you’re examining in your own work and trying to break open?

ADRIENNE

Particularly with Black women, there are moments of how we see people in entertainment–people like Josephine Baker–who become these iconic figures, but understanding how they exist in their day-to-day is something else. Josephine moved to France for a reason, because there was an inability to exist as a full human here. And there are other people like Dorothy Dandridge with similar experiences. It's not like I'm the first one thinking about them, but if you put all these stories together, it's about the sort of agency that Black women have and haven't had, the things they’ve had to contend with, the strategies they’ve had to create to manage their own visibility and invisibility. A lot of the themes of the work have been having hidden figures in these landscapes, and the whole tropical theme is its own tangent that I could talk about for an hour.

The invisibility/visibility portion is really this desire to give a bit more agency to the figure who can exist in a space without being immediately objectified or visible without being on their own terms. But then I also really love the strategic way that this idea of invisibility has been manipulated by people over the years. One of the things I think about a lot is Marie Laveau, which connects a lot to the tarot series in terms of the spiritual, voodoo hoodoo ideas. But one of the things I loved learning about her is that she had this whole aura of an all-knowing, mystical, psychic being. But so much of that was her recognizing that she was in certain levels of society and visible, and if she just stood there and listened, she learned everybody's secret. She's a slippery enough character that nobody has the actual story, but that's also what I love about it, this recognition that if nobody's looking at you directly, then you can be whoever you want to be and own the narrative in that way, which is kind of the crux of the way I'm trying to tell the stories with the characters and figures that I use in my work.

PLATFORM

I know you said you could talk about it forever, but I would love to hear you touch on the tropical themes that you mentioned at least a bit.

ADRIENNE

I give people a warning because I can talk about it for a long time [laughs]. I'll try to condense. The tropics came about for a few reasons. One, I will say there's this desire for people to desire the space of the work, and the tropics are this super seductive, desirable space. But they've been co-opted. There's a whole travel industry that's tried to create this aura of desirability around these spaces, but there's this whole long history.

To give some touchpoints, the spaces that are typically associated with Black and Brown bodies, looking at people like [Paul] Gauguin and [Henri] Rousseau and how those spaces have been exoticized through those narratives and those perspectives. Then there are things like the American South and the Global South and the Caribbean that have this throughline connection through the slave trade, but also through cultural exchange. In the years during and since the slave trade, there are things like food and traditions and cultures, religions, that have made their way amongst the sort of tropical landscape. They're not specific, or they don't have to be in these landscapes, but those are the associations with them. There are these histories that have come up in these spaces and that connect these global areas that might not be connected through nationality but are connected through some very tangible, less defined ways.

I had a show in 2020 that was called Escape and it was really about the travel industry and the co-opting of these spaces. Historically, in these tropical spaces, things like cash crops and capitalism, intense political and economic turmoil are brought there, and then these places are abandoned to contend with all of the issues that were left behind. Then the travel industry comes in and says, "Well, people want to feel like they're exploring." It's this idea of exploring. We could also say we're glamorizing genocide. It's the idea of feeling like you're discovering something or exploring something that is really the language that these travel companies use to entice you to. And I fall victim to that. When you dissect where this idea, this language comes from, it really connects back to this whole colonial, imperialist idea and making people feel like these places are ripe for the taking. It is there for your pleasure and your enjoyment as opposed to this place that has existed with this really rife, difficult history and is connected to all these other things.

PLATFORM

Just based on what you’re saying, it sounds like you're doing a lot of reading and research in this process. Is there anything that you stumbled upon that you found especially surprising?

ADRIENNE

There are so many things because history in American schools has woefully under represented most everything besides certain wars and white historical figures. One of the things that I continually point out to people, because it was surprising to me when learned it and seems to be surprising to almost everybody I tell it to, is the history of human zoos, which were a very regular practice. There are certain countries that were the worst perpetrators, like Belgium and France, and a lot of European countries, but America had them too. They would bring in people from other cultures and have them in a living landscape and have white people come and look at them.

Asia, Africa and South America were the biggest attractions. They'd bring people from these places and because this was post-slavery, people weren’t fully taken against their will, but highly manipulated under false pretenses and often had a hard time going back to their homes if they wanted to, or being able to afford any other kind of lifestyle. It existed openly for so long but we don't really talk about it. And there was one exhibit in the Bronx with a pygmy man until 1906. This is a 20th-century practice. It was next door.

PLATFORM

You’ve spoken a lot about ideas of place and land itself. Is there a space that you go to find inspiration that maybe people would find surprising?

ADRIENNE

I just moved back from Atlanta last year. I was there for two years, and I moved there right before the pandemic. I had lived there as a kid and my parents still live there. But I didn't expect to live there as an adult, and I wasn't really sure what work I was going to make while I was there.

I think that with the pandemic and also being back home near my parents, my family history there became a source of inspiration I didn't expect. One of my good friends in grad school curated me into a show and we did an interview together where he pointed out that a lot of my work had been made from an arm’s distance. I'm talking about these other people or I have a surrogate fictional character that I've created in order to talk about things so it’s not about me. But at that time, I was starting to make this work that was actually about my own history. He was like, "Now it's personal."

That was unexpected because I am used to doing research on historical things and if I want to talk about something personal, it has to be through this other figure. That was a moment where I made this series of paintings, the sort of main paintings called Namesake and then a series of studies on a plantation house in Georgia that has my family name. Because written documentation for Black people is nearly nonexistent, there's no real proof that my particular family was there, but my great-grandmother was in Georgia until she died. It was common practice for Black people to have the last name of the plantation owner, so there was this kind of direct history there. I did this research on this plantation and found that it still stands. There were all of these images on the internet, like real-estate walkthroughs of this estate with photos from the '90s. I was then in the middle of all of these ideas and things I research, and at the time, I was working on the Manifesting Paradise series and I was thinking about tarot.

The first 22 cards of tarot represent the Major Arcana, which are these archetypal moments of life, things like love and death and motherhood or fatherhood. There's this one card, The Tower, that I was having a particularly hard time interpreting in my own language. It's about destructive moments. It's a tower that's been struck by lightning and it's up in flames with people are jumping out of it. And it's not the card you want to get in a reading. It's not a pleasant card. I've never met a tarot reader who's like, "This is good." They try to make you feel okay because it looks bad. It wasn't particularly pleasant for me to want to think about too much. But then as I was contending with these pictures of this plantation, I was like, "This is the house that needs to go up in flames."

That was a surprising moment for me. I was actually very self-conscious of how much I was going to talk about the direct relationship between it and my own family history. There's a point where I was like, "I can talk generally about it just being a plantation house." But that wasn’t the interesting part about it. Long story short, I think something that I've thought about as I'm making new work is how much I need a distancing device and how much things can be directly personal.

PLATFORM

How does it feel for you to make that shift to creating work that perhaps you're hesitant about because the subject matter is so personal versus having something where there's a little more distance between you and it?

ADRIENNE

It's a great question and actually touches back on the beginnings of my career in art school. In undergrad, I actually was making really personal work from old family photographs. I found that having critiques when you're like 18-, 19-, 20-years-old, is weird. It was personal and I wasn't ready to have that conversation or understand what I was doing with it. I think the distancing element came from wanting to talk about things, but not wanting the conversation to go toward these people and elements that are directly connected to me. I think I'm returning to that with years more experience and wisdom and the ability to understand why I'm doing it. I think all the research before about other things and understanding how my personal history connects to it has been helpful. And it allows me to talk about it without it being the only thing I'm talking about.

PLATFORM

Switching gears a little, what do you do when you need to unwind from all the intense things that go into your work?

ADRIENNE

I run, do yoga. I like cooking a lot. I think the thing that clears my mind the most is just going for a run, being outside, even if it’s just going for a hike. I lived in Australia for a few years, so I love going for swim and that kind of stuff. I think being outside and just feeling small in comparison to everything else is a good check for any time feelings become overwhelming.

PLATFORM

I didn't know that you lived in Australia.

ADRIENNE

I did. Right after grad school, I was there for three years. That was part of the shift in the imagery to a lot of the overgrown tropical imagery in the work. I don’t use Australia or Australian history in my work, but it got me thinking because a lot of the tropical plants in Australia aren't native to Australia. A lot of native Australian plants look more desert-like, kind of weird, and don't look like anything we see in pictures of Sydney. Palm trees and banana leaves and all of those things were all imported there. Learning that history a bit made me think about these other spaces and how everything is cultivated to this idea. We have this idea of what these spaces are, but that's not its original form. And what is the origin of anything?

PLATFORM

What was it like living on the other side of the world and being so distant from where you grew up?

ADRIENNE

I think in some ways it was super necessary and needed. I recommend everybody live far away for a minute. Australia is not even that different as far as places I could have lived. They speak the language. They're a mix between British and American culture, so it shouldn't be that different, but it was this uncanny difference that I think was really useful to experience. You can't assume things about people and places. Being able to travel around Asia more easily was really nice. Ultimately, I moved there right after grad school and I think it was necessary for my own artistic development. It helped remove some of those voices in my head from grad school and just make work without feeling the pressure of somebody seeing it or judging it.

I showed [work] in Australia, but there was a bit less of an anxiety about it because my professors and the core people I knew were nowhere nearby. But it ended up being too far from everything I knew. And ultimately, I think my audience, the people who I felt were really interested in the conversation I wanted to have, were not in Australia.

PLATFORM

Expand on that for me, if you could.

ADRIENNE

I like working with students, and I talk to them about this too. There's this understanding as an artist that people need to like your work for it to be a sustainable career. But I don't think anybody should ever cater to an audience and try to make something they think someone else is going to like. It should come from you and what you make. I don't think you have to move to different cities to find the audience. The work you make will have an audience, but your audience might not be exactly where you are at that moment. The audience might not resonate with the work. Maybe it's about time and not even be about place. Maybe in five years, that conversation will resonate with people more.

But it was a pretty visceral recognition that the conversations I wanted to have weren't as relevant in Australia. I mean, there are not a lot of Black people in Australia. I knew every Black person in Sydney. That's not even an exaggeration. If I saw somebody on the street, from afar, I would be like, “I know you.” [laughs] And it’s not that other people can't be interested in it, but without that larger culture, it wasn't going to resonate as broadly anyway. It wasn't my audience, but there are great artists there and they have a great art scene.

PLATFORM

This might be a bit broad, but what’s something you're looking forward to right now?

ADRIENNE

I'm looking forward to some vacations. I haven't had a vacation in a long time. I really tried over the winter and failed to take a vacation. Last year, I was moving and I was starting a new job and had three shows happening at once. I really needed a break. And so I actually have some vacations planned now. So I'm excited to take some time to just chill and do whatever I want for some time.

"In A New Body Of Work, Adrienne Elise Tarver Sets A $21 Million Plantation On Fire" - Forbes Magazine →

By Brienne Walsh

Published on October 28, 2021

Adrienne Elise Tarver, "Manifesting Paradise: High Priestess 2,: 2020, ink, colored pencil and oil ... [+]

When the lockdowns due to the pandemic began in March of 2020, Adrienne Elise Tarver was living in Atlanta, Georgia. She couldn’t go to her studio, so she began painting small works in her apartment inspired by tarot cards, which have been used for divination purposes since the 15th century. “The world felt like it was ending, and tarot tells the future, so the idea of thinking about the future felt really comforting to me,” Tarver says.

Concurrently, Tarver was doing a lot of thinking about her own family history. Her paternal family is from Georgia, she spent part of her childhood in the state and her parents had retired there after raising her and her brother in Illinois. “I thought about being a black person in the South,” she says. “I’m in love with the landscape, the oak trees and Spanish moss and kudzu, but all of that is also evocative of the terrible nightmare of slavery. You can’t really remove the place from this double meaning.” She began doing some research on her family name, and found that there was a town named Tarversville — and an extinct one named Tarver — in Georgia. “In the history of America when a black person has a name that connects to a place it's generally because of the plantation where their ancestors were enslaved,” she says.

Adrienne Elise Tarver, "Namesake," 2021, Oil on canvas, 60 x 48 in

Her research led her to photographs of the former Tarver Plantation, which was owned by Henry Tarver from 1850 until 1897. Hundreds of slaves farmed his 5,000 acres of land. The plantation house, which features 16-foot-high ceilings and a driveway lined with live oaks, was recently refurbished, and is currently on sale for over $21 million. The listing mentions that sweet potatoes were grown on the estate to feed Confederate troops, and that it was used by a Kentucky horse breeder as her winter retreat until her death in 2013. No mention is made of the people who lived and worked on the land. Tarver printed out a photograph of the house and placed it on the wall with her studio alongside of some of her tarot card drawings. There, she considered their relationship to each other, and her own relationship to the past, and to the future.

In traditional decks of tarot, there is always a tower card that depicts a tower being struck by lightning and engulfed in flames. The “tower” symbolizes a moment of great destruction, but also, rebirth. “Looking at the Tarver plantation, I realized it needs to go up in flames,” she says. She began painting the plantation house not restored, but instead, engulfed in fire.

Adrienne Elise Tarver, "Manifesting Paradise: Tower 16," 2020, Oil pastel, ink and colored pencil on ... [+]

This effigy was the starting point for two exhibitions of Tarver’s work currently open in the United States. “Underfoot,” a site specific installation of wallpaper, paintings and studies, is open at the Atlanta Contemporary through January 9, 2022. And “The Sun, the Moon, and the Truth,” an exhibition of paintings inspired by the tarot, is open at the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum through January 2, 2022.

The exhibition at the Atlanta Contemporary is centered around Namesake (2021), an oil painting that draws on many small studies of the Tarver Plantation in flames. Tarver often mines thrift stores for old photographs that she uses as inspiration for characters in her paintings.

Adrienne Elise Tarver, "Eclipse," 2021, Oil on canvas, 48 x 30 in

Eclipse (2021) is inspired by a vintage photograph of a black nanny standing behind a white mother and child. In the painting, her features are almost obscured by the starchy whiteness of her uniform. The exhibition also features Work in Progress (2021), a portrait of a woman whom Tarver refers to as Vera Otis. She is a fictional character, inspired by another photograph from a thrift store. Vera, who in the portrait looks weary, and somewhat disdainful, serves as a surrogate for Tarver and black women in general, and appears often in Tarver’s work. “Black people's history wasn't important enough to write down, so it gives this open space of still being able to invent the narrative,” Tarver says. “Underfoot,” which also features paintings of a cotton field and a driveway lined in live oaks, reaches back in time to mine a history that has been whitewashed. “Here's a place and what are all the moments from this place that help clarify the context and meaning of it,” she suggests.

Adrienne Elise Tarver: The Sun, the Moon, and the Truth (installation view), The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, September 8, 2021 to January 2, 2022. PHOTO: JASON MANDELLA

The exhibition at the Aldrich, meanwhile, looks towards the future. Tarver realized that the luxury of thinking about the future is one that was denied to her ancestors and continues to be denied to so many black people in the United States today. “The simple idea of mattering enough to have your own life, to be valued, is powerful concept in itself,” she says.

Made in the summer of 2020, when Black Lives Matter protests were taking place around the country, the exhibition is dominated by small ink, pastel and colored pencil drawings that bear names of tarot cards. The tableaus within them are lush, strange, otherworldly. Nude figures, often androgynous, are held still within a sort of tropical paradise. Tarver left the South this past summer and moved back to New York. But if you look closely, you can see the kudzu and the palm trees of Georgia, those quiet groves dense with humidity and buzzing with insects, in her future.

Vera Otis also appears at the Aldrich, again with her head thrown back, bearing the same weary expression as her doppelgänger at the Atlanta Contemporary. At the Aldrich, her portrait is entitled “Weary as I Can Be” (2021) and shows her juxtaposed against a split background. To the left, a grouping of people silhouetted against the sun. To the right, a portal that leads to a lush grove. Here, Vera Otis is a sage, a time traveler, a goddess. Are the planes of the canvas behind her connected? Or do they remain separate, the portal a barrier that keeps humans from the garden of Eden?

“The fact that there is a future is a powerful statement in itself,” Tarver says.

To learn more about both exhibitions, visit the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum website, and the Atlanta Contemporary website.

To learn more about Tarver’s work, visit her website.

"Mining the Past, Mirroring the Present" - CFA Magazine - Boston University

BY TAYLOR MENDOZA | PHOTOS BY STEPHANIE ELEY

In Adrienne Elise Tarver’s Three Graces, a trio of women stand together in naked repose. Surrounded by sugarcane and banana and pineapple trees, they lean into each other: hands gripping hands, arms and heads resting on shoulders. It’s a seemingly peaceful scene—but the inspiration for the painting is mired in racism. Three Graces is based on a photo Tarver (’07) found online showing Black women who were exhibited in Europe in the 19th or early 20th century. In Tarver’s painting, the women’s expressions are solemn and shadows of palm fronds slash across their shoulders and faces, reminiscent of the bars of a cage; the foliage covers turquoise boxy forms, suggesting a constructed background.

Three Graces (2019) Oil on canvas 84 x 72 in. The painting is based on a photo Tarver found online showing Black women who were exhibited in Europe in the 19th or early 20th century. Adrienne Tarver

“There were human zoos all around Europe and America throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries,” says Tarver, an interdisciplinary artist whose work has been shown across the world and lauded by publications like the New York Times and Brooklyn Magazine. “We understand how wrong that situation is and how exploitative it is, and yet the way the women were posed, it reminded me of so many images I had seen through my entire education, which had been sculpted and painted by mostly European men.”

Tarver was particularly reminded of postimpressionist Paul Gauguin’s exoticized and idealized depictions of French Polynesia and the women who lived there. She says the trope of the sexualized tropical seductress is one that has influenced the perception of modern Black women and that she has explored in much of her art.

“My work for the past five years has really been about Black female identity within the Western landscape,” she says. For Tarver, Black femininity of the past and present are inseparable. “I was thinking about the dualities of how we have been made to exist within this context, from this domestic, silenced figure who’s supposed to fade into the background to this oversexualized tropical seductress on display, and figuring out the narrative to give women in these spaces more agency.”

Escape

Three Graces debuted in January 2020 in Escape, an exhibition of Tarver’s work at Victori + Mo, a contemporary art gallery in New York City. The exhibit showed how the history of colonialism continues to impact Black women, showing lush tropical landscapes, vacation photos, and cruise ads, as well as images of human suffering and exploitation.

Escape the Crowds (2019) Cut paper collage. In collages like this one, Tarver subverts imagery from the tourism industry, calling attention to its roots in slavery and colonialism. Adrienne Tarver

“I was thinking about the duality of the word ‘escape,’” says Tarver, who centered the exhibition on the tourism industry and its roots in slavery and colonialism. “Sandals resorts and all of these vacation places, they all use ‘escape’ in their ads. The idea that you’re escaping your normal life, you get to go visit this place for a moment and forget everything. It just felt so ironic, because, ultimately, these places were built upon slave labor. The people who were creating these seductive landscapes that everyone is trying to escape to would have loved to escape to freedom.”

Escape also included a projected installation of tropical vacation photographs from the ’60s and ’70s. Tarver says she wanted to play with the feelings of nostalgia the photos provoked.

“It’s easy to fall into the warm, fuzzy feeling of memory with that, and as you walk down this narrow hallway, there are these collages juxtaposing ads for cruise ships and resorts with historical imagery of plantation workers, domestic help, and slave ships, so it’s clear that this more lighthearted thing is not as it seems.”

Head Above Water (2018) Oil on canvas 84 x 72 in. New York Times art critic Jillian Steinhauer wrote that the painting first connoted “glamorous freedom,” but after seeing works like Three Graces, “instead of seeing a scene of luxury, I imagined one of the women swimming to freedom.” Adrienne Tarver

The first painting viewers saw as they entered Escape was Head Above Water, which shows a woman’s legs dangling as she floats in sunlit water. Her crisp white bathing suit bottom contrasts with her brown legs. In her review of the show, New York Times art critic Jillian Steinhauer said when she first saw the painting, it suggested “glamorous freedom,” but after seeing the slideshow and works like Three Graces, “instead of seeing a scene of luxury, I imagined one of the women swimming to freedom.”

Art and Identity

Photography has long been an important part of Tarver’s art. While Three Graces was influenced by a photograph she found online, much of her earlier work was inspired by family photos—in particular those of her older brother. He died when she was 16.

“I painted a lot of photos of him, of him and me, of my family,” she says. “I went to a summer program at the Art Institute of Chicago and made this series of 16 small paintings all arranged together of different parts of my brother’s life.”

Tarver teaches at the Savannah College of Art and Design’s Atlanta campus, where she is the associate chair of fine arts.

Although Tarver had initially thought of architectural design as a potential outlet for her creativity, her brother’s death prompted a fresh look at her plans. “I was really understanding how short life is,” she says. “I really don’t know if I would have pursued art if that hadn’t have happened.”

“IT’S NOT POSSIBLE TO SEPARATE MY EXPERIENCE AS A BLACK WOMAN FROM MY ART, BECAUSE SO MUCH OF MY ART IS ABOUT MY EXPERIENCE.”

At CFA, Tarver shifted away from portraits of her family—“I couldn’t separate how people talked about the art from what I felt about my family”—and began to use her art to explore what it meant to be Black and female in America.

“I got a bunch of old silver platters and silver serving things and I started doing a lot of self-portraits. I balanced the tray on my head with the objects, taking on this character of a house servant. I was diving into this history of who I was to America—the domestic woman.”

Now an associate chair of fine arts at Savannah College of Art and Design in Atlanta, Ga., Tarver says her identity as a Black woman continues to be essential to her work. “It’s not possible to separate my experience as a Black woman from my art,” she says, “because so much of my art is about my experience.”

Projecting Futures

Escape closed on March 14, 2020, around when New York placed coronavirus-related restrictions on its residents. While Tarver had some downtime in the wake of her exhibit closing, the uncertainty of coronavirus and the resurgence of the Black Lives Matter protests have inspired her to explore the ideas present in the exhibition, as well as what the future means to Black people.

“The longer we were in this situation, the more unknown it became, I thought a lot about fortune-telling and tarot,” says Tarver, who began studying the stories of—and attitudes toward—Black women like famed New Orleans Voodoo priestess Marie Laveau and TV psychic Miss Cleo. “There’s this idea of the Black woman holding some sort of deep wisdom or mythology, so there’s always a separation between this world and their world. In a moment where there’s so much uncertainty, I think people fall back to religion or astrology, just because nobody else can tell them real answers.”

This summer, Tarver started making her own tarot cards. Using ink, oil pastel, and colored pencil, she created a series of vibrantly colored images inspired by Afrofuturist ideas and imagery of the tropics. The titles of the works share the names of cards typically found in a tarot deck, such as High Priestess and Chariot. In Strength, a woman sits perched on an elephant’s trunk. Both woman and elephant are painted in washy ink, starkly contrasting with the bold yellow sky behind them and the bright blue ground beneath them, which is thickly built up with pastel. Tarver will eventually make these images into a printed deck of cards.

“It was this understanding that saying that we exist in the future—that there’s a future for Black people—is actually a radical statement,” says Tarver. “This idea of projecting futures, of telling fortunes, is a radical idea in and of itself, and telling somebody that you will exist tomorrow is a really heavy statement when you are consumed with how unpredictable life can be.”

"I Like Your Work" Podcast

It was fun to be interviewed by Erika Hess, artist and creator of this great podcast. You can find the episode wherever you get your podcasts or via the podcast website:

Editor's Pick: 17 Things Not to Miss in New York's Art World This Week

9. “History Reclaimed: Suchitra Mattai and Adrienne Elise Tarver” at Hollis Taggart

Suchitra Mattai and Adrienne Elise Tarver both make undeniably beautiful work that is unafraid to address a challenging history of colonialism and racial oppression. Mattai has created a new site-specific large-scale installation for the exhibition using hundreds of vintage saris. Tarver is showcasing two paintings series, one of portraits of black women, both archetypal and historical, and of tropical foliage that spills off the canvas, disrupting the white cube of the gallery. (It’s something of a moment for Tarver, who also has a solo show, “Escape,” at Victori + Mo , also in Chelsea, through March 14, and work in the new, hands-on “Inside Art” exhibition at the Children’s Museum of Manhattan.)

Location: Hollis Taggart, 514 West 25th Street

Price: Free

Time: Opening reception, 6 p.m.–8 p.m.; Monday–Friday, 10 a.m.–5:30 p.m.; Saturday, 11 a.m.–5:30 p.m.

—Sarah Cascone

"Escape" reviewed as a show to see right now by the New York Times

The first artwork you see upon entering Adrienne Elise Tarver’s third solo show at Victori + Mo is a painting of a woman’s lower body under water. Her white bathing suit and brown legs float amid ripples of navy, grayish blue, and aquamarine. The piece, “Head Above Water” (2018), suggests glamorous freedom — but by the time I encountered it again on my way out, I understood it differently.

The exhibition plays on two meanings of its title, “Escape”: a vacation getaway and breaking free of bondage. Ms. Tarver connects them via the tropics, a frequent subject of hers and a region where idyllic beaches can mask histories of colonialism. In a series of small collages, she frames historical images of enslaved people and plantation workers within advertisements for cruise lines. They are cutting.

The highlights, though, are Ms. Tarver’s paintings, which are capacious enough to evoke ideas of voyeurism and exoticization alongside beauty. “Three Graces” (2019) is a life-size depiction, based on found photographs, of three women who were kept in 19th-century human zoos. Posing amid lush foliage, they look forlorn yet dignified. I thought of them when I returned to “Head Above Water.” Now, instead of seeing a scene of luxury, I imagined one of the women swimming to freedom.

JILLIAN STEINHAUER

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/20/arts/design/art-galleries-new-york.html

"Inside Art" in the New York Times

Read the rest of the article HERE.

#ArtPowerWomen Series: Adrienne Elise Tarver

December 10, 2018 by Art Zealous

For this month’s #artpowerwomen series, we sat down with Adrienne Elise Tarver, an interdisciplinary artist based in Brooklyn who’s installation Origin: Fictions of Belonging is creating a lot of Art Basel Miami buzz. Be sure to stop by PULSE art fair and experience Tarver’s piece in which she connects draping sheets of intersecting palms and leaves on wire mesh that hang from the ceiling. It’s not to be missed!

We picked Tarver’s brain about her work, being a feminist and why she is so drawn to the tropics.

HH: When AZ first profiled you in 2016, your work centered on the narrative of a character you based on a found photo named Vera Otis—from the Latin veritas—as a reminder that nothing presented in narrative is completely true. What’s Vera doing now?

AT: At that time, Vera was in the process of moving from the house featured in the “Eavesdropping” series. I don’t know exactly where she is going to end up after that move, but she’s in transition now, searching for a home and popping up in places that she’s connected to in some way. I think a lot about non-linear narratives and part of developing her narrative is connecting parts of her past to things that resonate with where she might be presently.

AZ: Miami or New York?

AT: New York–but you have to escape it every now and then to enjoy it.

HH: How has your exploration of voyeurism evolved?

AT: I still think about the role of the viewer, the boundary that turns someone into a voyeur, and the truth the voyeur will never know, but I’ve been more interested recently in the perspective of the viewed. I’m interested in the multiple perspectives that combined create the scenario of watching or being watched. I think a lot about how we hide or camouflage.

HH: In the post-truth era, when there’s tremendous social anxiety about what we can know with any certainty, your work could add to that anxiety. How does your practice offer us hope?

AT: I’m not sure I can offer hope. I hope to start conversations. One of the things I think about a lot is the cyclical nature of history–we repeat mistakes and revive ideologies, sentiments, desires, and fears. Truth, which is fickle and hard to pin down anyway, is easily lost as we cling to what is familiar. Since everyone has their own idea of truth, I think the first step is a conversation–listening, hearing different perspectives, searching for the other side of stories we’ve been told one way over and over again. I think just by being a black woman in America I’ve been aware as long as I can remember that the history books I grew up studying in school were leaving out a large part of the story. I think any artists’ practice that seeks to add more multi-dimensional stories into the world provides a starting point.

AZ: When is your favorite time to make art?

AT: I’m generally a morning person, but when I get into a groove in the studio I can stay pretty late.

BW: Your work right now is focused on the idea of the tropics. Why are the tropics so seductive to everyone?

AT: I think the tropics have an allure that’s hard to deny because the narrative that’s exported eliminates unsavory aspects of the history and reality of living there. It’s been distilled down to an idea of a place. We’re inundated with ads for islands that present these places as yours for the taking. Sun, sand, food and friendly locals are there for you, to provide you with an escape and to take your stress away. We accept this oversimplified idea of a place because we desperately want what the ads are offering. It’s easier than engaging with real current issues or traumatic pasts.When I was in high school, in the Chicago suburbs, I was at a hair salon that I had gone to for years. It was the middle of winter and a woman I had known for as long as I had been going there, and knew to be born and raised in that area, commented on how much she hated the cold Chicago winters and said, “We really are a tropical people, you know.” That sentence stuck with me because I think it speaks to a few different things: the desire to know a longer history of yourself than the one you’ve lived, the seduction of the tropics as a foil or cure to urban or suburban life, and a denial of traumatic and difficult realities of that history.

BW: You’ve been inspired by Paul Gauguin and Henri Rousseau. As a feminist and a woman of color, how do you navigate the work produced by white men who deliberately objectify women and glorify colonialism?

AT: I’ve grown up appreciating and in some cases really loving work by artists that I find very problematic now. I love Paul Gauguin’s paintings for example, but not his objectifying and fictionalized perspective of the tropics. I think it’s similar to what’s happening with the #MeToo movement and how we are grappling with the creative work of men in Hollywood who are being outed as predators. I don’t think the bodies of work by these men should be stricken from the record (erasing history is the easiest way to repeat these mistakes), rather I think they need to be counteracted and/or responded to by women, people of color, people of different sexual and gender orientations, and from varying perspectives. We can make problematic narratives smaller by elevating people and voices that have historically not been able to speak alongside them.

HH: You make work in many different media (paintings, video, collage, sculpture, photography, etc). Do you have a favorite and why?

AT: I’ll always identify as a painter first and foremost. Sometimes painting isn’t the medium I need at the time for the idea I have, but there’s always a painterly sensibility to what I’m doing. Whether that comes across in the color, composition, or materiality, it’s there just under the surface.

BW: You tend to work in either super large scale (like your current installation at PULSE) or super small scale (your current watercolor show at Ochi Projects). Why doesn’t there seem to be any in-between in your practice?

AT: I think it’s a matter of thinking about intimacy and confrontation. Voyeurism and truth have been constant themes in my work and both of those things operate fully and differently on these polar opposite scales. If I make a miniature and force you to look closely at the detail, you’ll enter that work with an intimate distance. Same with the watercolors and oil paintings at Ochi Projects right now–they entice you into an intimate relationship. But I’m also interested in the overwhelming seduction of a space–changing your perception due to shift in scale, saturation, material experience. In both the small-scale work and the large-scale installations there’s a question of your body and how it relates to the thing in front of you. That self-awareness is something I like to exploit.

AZ: If money was no object, what’s your dream project?

AT: I’ve been thinking a lot about public spaces and bringing the work into parks or large empty spaces. I’d love to do a very large hanging painting installation (similar in idea to “Origin” at PULSE currently) but I’d love to include performers and incorporate the wearable sculpture pieces I’ve been making.

AZ: Tell us about the installation you’re exhibiting during Miami Art Week at PULSE.

AT: The piece in PULSE is called, “Origin: Fictions of Belonging.” It connects draping sheets of intersecting palms and leaves on wire mesh that hang from the ceiling. These hanging transparent works started from thinking about “veils” from W.E.B. DuBois’s description in ‘The Souls of Black Folk’ of the invisible boundaries that exists between us. It requires viewers to dip under and walk around it, tapping into the imperialistic impulse to explore and the notion of discovery that created an appetite for tropical narratives. The overly saturated, non-specific, tropical greenery, highlights the oversimplified narrative that we accept to represent much more complicated histories.

You can view Adrienne’s work on Curatious.

New Takes: Adrienne Elise Tarver

By Jamee Crusan March 13, 2018

New Takes (formerly Fan Mail on Daily Serving) is a column that spotlights emerging artists from every region on this planet. Art Practical welcomes all artists to submit their work to be reviewed. Every year, a writer is nominated and selected from a pool of recent graduates of California College of the Arts to write for the New Takes column.

The Brooklyn-based interdisciplinary artist Adrienne Tarver’s seductive jungle landscapes blur the lines between looking and voyeurism, pulling viewers in and out at her command. In her latest work, Botanica Magica (2017), featured at Pelican Bomb Gallery X in New Orleans, Louisiana, Tarver explores the jungle landscape by using a rich color palette of ink on durable yupo watercolor paper. Viewing Tarver’s 8-feet-high, 34-feet-long painting is a full-body experience. The tropical trees tower over viewers, and the span of the painting, which reaches across three walls of the gallery, further envelopes the audience in the tropical paradise. Tarver transports viewers into a beautifully painted jungle full of green, blue, brown, and yellow hues. However, a closer look reveals the hidden curves of bodies—hips, thighs, and breasts—immersed in the foliage. Tarver provides viewers access to these hidden figures but only if they are willing to look long enough, hard enough, to see these abstract figures.

Tarver told me that to create the Black and Brown female bodies for her “land of women,” she pulled inspiration from classic archetypal figures including nymphs, muses, and sirens, calling them “seductive, dangerous, and elusive.”1 Through her skillful blending of lush and vibrant inks, Tarver creates a visual conundrum for viewers, asking them to oscillate between two roles of looking: that of the onlooker and that of the voyeur.

Where is the line drawn between the two? Voyeurism is defined by the Merriam-Webster dictionary as gaining sexual pleasure through looking,2 whereas simply looking speaks less to pleasure but still connotes a power dynamic. Tarver further implicates viewers by compelling them to interact with the highly sexualized Black and Brown bodies, always already exoticized, in a fertile, precarious, and alluring environment; the idea of the jungle, too, is loaded with connotations of conquest, primitivism, and colonial rule. These concepts of the exotic are simultaneously transferred between landscape and bodies.

Tarver posed the question to me, “At what point do we decide somebody deserves respect and to not give into our own curiosity but respect someone’s personal boundaries?” There is play within the visibility of the multicolored bodies that are shrouded in the landscape, rendering some figures invisible unless the watercolor image is carefully studied. This act of examining the bodies of Black and Brown women elicits the voyeuristic history of the colonial gaze, and as a viewer, I found myself suspended in this exacting tension Tarver ignites in her work.

When I looked at Botanica Magica, I noticed a meticulous thin white line that traced around bodies and leaves, a detail that confused my eyes in an already stimulating scene. Just as I started to think there was consistency in the placement of the white lines, I soon noticed that was not the case. I was led from tree to tree by the white lines, yet when I followed them, I couldn’t see the woman’s body directly in front of my face. It's here, in the spaces between lines and boundaries, where Tarver’s blurring—of sight, and of my role as viewer—occurred. Standing back, I observed how some bodies appeared to be engaged in private, intimate acts while appearing to be in ecstasy or even bathing in a river. I realized that the strong trunk of a tree was in fact a thigh, and what I first believed was a leaf transformed into an arm. Tarver blends and hides these eroticized bodies, thereby luring viewers deeper into the landscape, compelling them to keep looking. I continued staring into the jungle while allowing myself to be enticed by the danger of the siren’s song or a forbidden landscape.

Tarver continually returns to the tropical jungle landscape and the power of the gaze in her work. In Veil (2014), she again creates an overwhelming environment that elicits sensorial confusion while actively engaging and confronting the viewer. Hanging from the ceiling, a large mesh screen covered in white acrylic caulking depicts a jungle scene. Measuring 8 feet high and 4 feet wide, the acrylic surface also serves as a site that receives the projected video footage of jungle foliage. Against the gallery’s dark atmosphere, the projected imagery of bright, vivid greens generates an immersive environment that produces visual disorientation. As an onlooker, I felt drawn into the seemingly haunted tropical landscape, and then felt surprised as I caught sight of a figure standing in the shadows. Eventually I realized the body was camouflaged into the physical acrylic painting; in the shadows, she blended in with the foliage around her—a figure almost invisible, since she was created by the white caulking. In Veil, viewers are trapped in-between looking at the projections of light, the overlapping jungle-scapes, and shadows. It’s hard to stay grounded between light and dark, and Tarver plays with this. She has created an environment in which two spaces converge into each other, and the woman’s body resides in both. I continually oscillated in between the two worlds, hovering in sustained uncertainty.

There is power in the gaze, and as many scholars—bell hooks, Edward Said, Kobena Mercer, and Frantz Fanon—argue, the gaze is already voyeuristic since it is rooted in a hegemonic perspective, more often than not specifically white and male. The jungle landscapes are continually exchanged with the Black and Brown women’s bodies, an act by Tarver that allows the cultural projections of the jungle’s exotic, dangerous, and wildly untamed nature to be associated with or projected onto the bodies. In this exchange, Tarver mediates exposure in her jungle-scapes while simultaneously, unabashedly implicating the colonizer’s gaze. Tarver commands and controls the way in which the viewer sees the bodies of the women, and even how they are accessed. The women are exposed with naked bodies, as seen in Botanica Magica, and with stark white light creating the shadowy figure as seen in Veil. Tarver gives the viewer very little information about the women she shows and also hides, which allows viewers to project any story or idea onto the figure. By controlling how the bodies are seen and recognized as the exposure of these women’s identities, Tarver creates an invitation for viewers to consider, wondrously or voyeuristically, who these women are, but she reminds us there are some things we don’t get to know.

MINOR HISTORY X ADRIENNE ELISE TARVER →

Adrienne Elise Tarver is an artist living in Prospect Heights, Brooklyn. Exceedingly bright, charismatic, inventive, and engaging, speaking with Adrienne is like relaxing on your favorite leather couch with an old friend and a good glass of wine. We suspect that everyone she meets feels this way.

“Everyone has a perspective… I think about the uniqueness of perspective and the inability to find a singular truth when recounting history, we all have unique ways of seeing things and experiencing the world informed by our lives, identity, and history. These are things I think about in my tropical works and the work that revolves around the story of [a fictional woman] Vera Otis... I connect memory to this [because] the memory of a place, object or material informs our perspective and changes the narrative we create.”

That’s a fraction of insights discussed during a casual conversation about history, mythology, colonial legacies and her collaboration with Minor History. From kid entrepreneur to imaginative artist, her work challenges the idea of materials, artforms and conventional executions.

“Before [graduate school] I had always had this separation [in my practice] between ‘fine art’ and ‘the craft part.’ I grew up sewing and there would always be fabrics at home and wood, and I had never considered them as being in the work.”

Now, Adrienne’s interdisciplinary art practice is deeply embedded in the materiality of the everyday object. She realized the beauty and visual stimulation provided by childhood crafts, noting, for example, that she “sewed as a kid—made my own purses… I also had a friendship bracelet making business during summer camp. People would select their colors and I’d make the design and create the bracelet. Then in 5th grade, I started a pencil decorating business— in general, I always had a lot of arts and crafts around.”

Reconsidering her craft and art practice, Adrienne says that after grad school she was “fully [able to] accept the idea that anything can be a[n art] material. I have no hierarchy in my brain about it.”

Yet it was her training in fine art at Boston University and School of the Art Institute of Chicago that is the foundation of her mature work. This blossomed into a hybrid of materials and inventive techniques that break the mold of traditional canvas and paint for a three dimensional, painterly experience. She makes use of her childhood training in craft, her endless curiosity, and her intuitive sense of architectural space in her most recent work: large-scale installations of densely painted plants.

Adrienne’s recent installation at Victori + Mo gallery reinterpreted traditional trompe l’eoil through materiality. It used wire mesh as a support structure for thickly painted tropical and domestic plant images that interrupt our normal experience of the reality in her installations, forcing viewers to physically engage by ducking, weaving, and climbing over the pieces as if wading through the dense fauna of a jungle environment. Yet these plants appear ethereal. The painted vines and leaves hover, magically unsupported. “When we see a window we tend to omit the screen. It’s easy to ignore what’s actually in front of you.” Adrienne explained that the perception “of delicacy overlooks a very strong material.

She employs this same playful approach in the design of her leaf clutch for Minor History. The clutch, directly inspired from components of her work in the Victori + Mo Show, appears delicate and ephemeral but it is made out of durable, reliably crafted material that only improves in quality over time.

“I loved the idea of making a Minor History bag so much because these bags will grow into your perspective with you. They become unique to you, to your experiences. They develop into souvenirs of moments and migrations and life.”

Material objects, according to Adrienne, hold onto the memory of those people that held onto them. Material takes the impression of the time and the people that happen around it. This can be painful and pleasurable simultaneously; the past is present in our senses. In touching, looking, living with our objects, we both revive history and create it.

Her line of Minor History bags display the playful urgency with which she approaches her subject: the camouflaged wilderness in the domestic. Gentile, feral, and ultimately, beautiful.

Adrienne is currently a resident at the Lower East Side Printshop and works as Director of the Art & Design department and of the HSA Gallery at the Harlem School for the Arts (HSA). “Every teacher has a favorite age,” Adrienne admitted, “mine is late middle school to early college. The teen years. I like that age because students are intelligent, they’re excited, and they are still very open to ideas, but they’ve developed the skills to build on things. They surpass you in so many ways, which is exciting to me. I want to be impressed by my students, and I am, constantly.”

You can find Adrienne Tarver's artwork in her show at Wave Hill, on view this spring. Follow her on Instagram for more updates @Adrienne__elise.

INTERVIEWED WINTER 2018 BY KRISTEN RACANIELLO. PHOTOGRAPHY BY AMBER MCDONALD

Assuming is Dangerous: Talking with Gowanus-Based Artist, Adrienne Elise Tarver

Covering tropical landscapes, immoral behavior, and the allure of mystery.

BROOKLYN MAGAZINE - March 2017

In almost every context, white men are the only makers afforded a blank canvas; everyone else gets qualified. When these qualifications (black, female, gay, on and on) bubble up without context, assumptions can take over the reading of the work—assumptions that the artist intended to employ the politics of race, of being female, of being anything other than an artist making work informed by, but not restrained by, their identity. It’s the ancient blunder of making an ass out of u and me.

When I talked to Adrienne Elise Tarver about what she’s been making, I wondered if these assumptions plagued her. They do, and it has influenced her work: Adrienne experiments with the powerful, mysterious force of the unknowable and the potentially destructive actions of claiming (or gaining) access to what’s not yours.

In the first of Adrienne’s two solo shows at Victori+Mo in Bushwick, the enigmatic Vera Otis was moving: miniature displays of her home were tucked into cardboard boxes with slits for viewing; quiet, shadowy videos looped all around. In the second show, Secrets of Leaves, which opened in late February, the idea of voyeurism moved to the jungle. We’ll walk inside walls of leaves, looking for hidden figures—but in a reversal, we’ll also be captured by Adrienne. She built this leafy cage for us.

For all the mystery, Adrienne is incredibly open and matter-of-fact. We met over Thai food (she ate her fried spring roll with a fork and knife, claiming she doesn’t usually do that; I ate with my fingers, burnt my mouth, then the roll fell apart), and then continued the conversation a few days later over Google chat. Here’s a portion of our conversation.

You told me that your work has been politicized without you intending for that.

I assume it’s because of my gender and/or race—I think it’s an easy opening and there are a host of assumptions people come to the work with if they know my gender and/or race. I mean, I started to think about these assumptions so much that it worked itself into my work—these ideas of intrusion/privacy and what we think we see and what we cannot see. I think it’s an interesting conversation for me to think about my work being politicized instead of talking about politics in my work.

What do you hope people see?

I hope to draw attention to the narrative the viewer is creating. That what you’re seeing is not necessarily what exists. I think in real life (and I’m including myself in this) we don’t question the conclusions we’re drawing often enough, and I think that has varying degrees of implications and problems. I guess I hope people are enticed to look and are either surprised by what they see or want to create their own narrative.

Let’s talk about your shows! Can you describe what your second solo show will be like, and how it will differ from the first?

Yeah: it’s peeking inside a private, domestic space [Stories of Shadows] versus exploring a tropical landscape [Secrets of Leaves]. The spectrum of intrusion is the most succinct way for me to explain how these two shows/bodies of work connect.

On one end of the spectrum, there is the innocuous intrusion of peeking in a window, probably undetected and letting yourself linger long enough to draw conclusions and maybe create a narrative about the person/people you see inside their private space. On the other end of the spectrum is taking this “permission” to look inside to the extreme and entering an inhabited space to claim for your own. This is where I’m looking at imperialist histories, ethnographic expeditions, human zoos etc.

The house photos/videos look at the tropes of film noir—Hitchcock’s Rear Window is probably the most direct example—and how intrusion is used as entertainment. But as I say that, I’m careful not to place too much judgement, especially on the low end of the spectrum. I’m nosey as hell and I am very guilty of looking in people’s windows when I walk down the street at night. I think we all fall on this spectrum somewhere and I’m curious where we might trip into immoral behavior.

I’m also curious about where I make assumptions about other people and what I cannot see or know about them. On the one side there’s an allure of mystery, and on the other side there’s the danger of assumption, especially when it comes to identities.

14 Emerging Women Artists to Watch in 2017 - Art Net News

Who runs the world?

Sarah Cascone, December 21, 2016

Adrienne Elise Tarver. Courtesy of Adrienne Elise Tarver.

14. Adrienne Elise Tarver

The subject of the just-closed solo show, “Stories of Shadows,” at Brooklyn’s Victori + Mo, Adrienne Elise Tarver has created a fascinating series of work, all stemming from a found photograph of a black woman in glasses. Tarver has invented an entire life and persona for her unknown muse, who she has christened “Vera Otis,” exploring issues of voyeurism through video “vignettes” and dioramas. In an era where the concept of privacy is fading fast, Tarver’s work calls into question the divide between appearances and reality.

“it doesn’t matter who she is,” Tarver told Art Zealous of Otis. “With us both being black women, she has served as a vessel or surrogate for me to ask larger questions or tell stories that relate to me and my experiences or the experiences of women in my life.”

Voyeurism & Stories of Shadows with Artist Adrienne Elise Tarver - Art Zealous

December 15, 2016 by Kristina Adduci

Photo credit: John Ma

If you do one thing before you leave town for the holidays, it should be to go check out Adrienne Elise Tarver’s newest show, Stories of Shadows at Victori + Mo. With this exhibition, Adrienne Elise Tarver expands upon the narrative of Vera Otis, a character based off of a black and white portrait photo she found of a woman in a thrift store. Tarver named her character Vera derived from the Latin word veritas for truth as a reminder that nothing in presented narrative is true.

We caught up with Tarver to discuss her background, influences and voyeurism.

Art Zealous: Tell us about your background and how you came to be an artist?

Adrienne Elise Tarver: I grew up involved in all of the arts— through my teens I danced, played the flute, and made visual art—I was also very crafty, I sewed and built things. In high school, I won an award to attend a summer program at the Art Institute of Chicago which solidified my love of making art and my drive to become an artist. I didn’t really know it was possible or what it entailed until then. From there I received my BFA at Boston University, then after a couple of years went back to the School of the Art Institute of Chicago for my MFA.

AZ: Coffee or tea?

AET: I’m a heavy green tea drinker and love all things green tea flavored. I love both coffee and tea but can’t handle the caffeine in coffee though I still have coffee ice cream and very occasionally sneak a decaf mocha.

AZ: Biggest influence in your life?

AET: My older brother was and still is a huge influence in my life. He passed away when I was in high school and many of the decisions I’ve made since then, especially in regards to pursuing art, come back to him. All of the cliches about realizing how precious life is, living life to the fullest, and doing what you love really resonate with me because of losing him.

Adrienne Elise Tarver, Eavesdropping 1, 2016 digital photograph of built miniature sizes are variable Courtesy of the artist and Victori + Mo

AZ: What object have you held onto forever that you can’t bring yourself to get rid of?

AET: I’m very sentimental and like to keep mementos, so there are many. One of the most significant is a watch my brother gave me—it stopped working years ago despite attempts to get it fixed, yet I still have it.

AZ: Do you listen to music while you work? What’s on your playlist right now?

AET: I mostly listen to podcasts while making art (This American Life, RadioLab, 2 Dope Queens, Savage Lovecast, Snap Judgement, The Moth) and music while I run (either the Beyonce or Azalea Banks Pandora stations have good running tempos for me).

Adrienne Elise Tarver, Eavesdropping 5, 2016 digital photograph of built miniature sizes are variable Courtesy of the artist and Victori + Mo

AZ: How would you define voyeurism and what role does that term play your work?

AET: I would define voyeurism as a form of intrusion—it starts with looking in without your presence being known, but can become a lot more. To be a voyeur is a position of privilege and power, which is why I think I find it so interesting. Also, the idea that being a voyeur does not mean that you are immune to being viewed. Looking in on someone else makes you aware of your own vulnerability. It’s this fluid power dynamic that is unsettling and uncomfortable. Everyone has a moral and physical boundary—a point where they decide they are in fact intruding and usually look or walk away. This point varies for everyone. I like to pull at the desire to be a voyeur to see how far the audience will go.

AZ: Is there an artistic medium you’ve never tried before that you want to learn to use?

AET: I’ve been thinking lately about welding and metal casting—more relating to my hanging foliage paintings—I’m thinking through ideas of durability in public spaces.

AZ: What do you want viewers to take away from your upcoming show Stories of Shadows?What is the significance of jungle imagery in your work?

AET: I want viewers to feel the intimacy of the space and question their right to look into this woman’s life. I look at voyeurism existing on a spectrum of intrusion—with looking into your neighbors window being one of the lesser transgressions. The tropical foliage exists on the other side of this spectrum, tapping into a more imperialistic form of voyeurism rooted in an assumption that what or who is within and beyond the dense tropical flora is ‘undiscovered’ and open to being claimed and consumed. I think a lot about artists like Henri Rousseau or Paul Gauguin who participated in fetishizing those landscapes and their inhabitants. I’m also fully aware of how I am susceptible I am to being seduced by the tropics—it’s more about raising questions than inducing guilt for this desire.

Adrienne Elise Tarver, Eavesdropping 8, 2016 digital photograph of built miniature sizes are variable Courtesy of the artist and Victori + Mo

AZ: Who is Vera Otis and what do you have in common with her? Did you consider other names for Vera?

AET: Vera Otis is a character created from an image of a woman in an old photograph. In reality, it doesn’t matter who she is, just that I don’t and will never know her real story. With us both being black women, she has served as a vessel or surrogate for me to ask larger questions or tell stories that relate to me and my experiences or the experiences of women in my life. Although I didn’t name her for a while, there was really only one name that felt appropriate—Vera means true in Latin or real in Italian. I was always playing with what is true or real—something the audience (or I) can never accurately assess as voyeurs. The power of the voyeur I spoke of before, is always based on fiction.

AZ: Favorite Brooklyn spot to grab a bite after a long day in the studio?

AET: My studio is two blocks from Four and Twenty Blackbirds which has a great Mint Green Tea Latte and great scones and biscuits. Also pie and other treats.

AZ: Dream location to show your work?

AET: I fell in love with art at the Art Institute of Chicago. It would fulfill all of my childhood dreams to show there.

AZ: What’s next for you?

AET: I have a lot of ideas for Vera Otis. In the current work, she’s moving out of the house we’re looking into in “Eavesdropping.” I want to explore where she came from and where she is going next. I don’t have answers for that yet, but I have ideas for more work exploring these questions. In February, I’m excited to create a physically engaging installation of the tropical work at Victori+Mo.

http://artzealous.com/voyeurism-stories-of-shadows-with-artist-adrienne-elise-tarver/

Stories of Shadows is on view at Victori + Mo, 56 Bogart Street, Brooklyn, NY

December 8-December 18, 2016

The Numinous Artwork of Adrienne Elise Tarver - Peripheral Vision Arts

Wednesday 01.11.17

Peripheral Vision, no. 2, 2016

by Lisa Volpe

Adrienne Elise Tarver, Eavesdropping

Numen is the best word. Though this term—drawn from Roman paganism—is far removed from our contemporary context, it remains the best description of the method by which artist Adrienne Elise Tarver’s project succeeds. A numen is a spirit, especially one believed to inhabit a particular object. Though the word might seem foreign or antiquated, the concept is familiar, even in our digital age. We all have a tendency to collect numinous objects: the tassel from your graduation cap, a pressed flower from a romantic date, or a scruffy teddy bear that is emblematic of childhood. Numinous objects “concretize [the] abstract.”[1] With these objects, concepts such as being, time, and/or memory are embodied in the tangible. This connection is not inherent; instead it is created and can die away. A numinous object exists as long as a single person remembers the connection between the object and the significant person, place, or event it references. In the same way, a numen loses its power when all those who remember the association are lost.[2]

Numinous objects reveal more than memories, they speak to psychological needs. Psychologist Paul Bloom argues that the history of an object changes how we experience it. Bloom emphasizes that our pleasure with an object increases with knowledge of its history.[3] In short, we desire objects with history. In her work, Tarver builds upon this connection between objects, history, and desire in order to investigate issues of transgression and voyeurism. In her multi-media installation, Eavesdropping, Tarver constructs and presents a host of numinous objects, making concrete the abstract concepts of knowledge and desire.